Having worked on more than 1,500 projects across the world, we know what it takes to transform a vision into a tangible concept—and then develop it from drawings on a screen to a venue that serves a purpose for its community. Every one of our projects has a set of constraints—from budget and site limitations to varied programming needs or the specific quirks of an existing structure. These constraints don’t just help to set the ground rules for our work, they challenge us to be creative.

With a clear understanding of a client’s vision and ambitions, we start the creative process of imagining how we can meet their needs through planning, design, and technology. But truth be told, that’s only part of the story. We also use project parameters to help guide us in finding those solutions. If we have a great idea, but it doesn’t fit within the parameters, it’s simply not the right solution. So, we go back to the drawing board and keep working at it until we find something that truly works within the constraints.

We start this process even before we start to sketch out a design. It begins with an appraisal of our client’s needs and expectations, followed by an analysis of how we can realistically achieve them within their budget. “Realistically” being a key word there. The big ideas and the client’s real-world needs have to exist hand-in-hand.

A client may have a total budget of, say, $50 million. On the face of it, that may seem like a large investment to spend on a capital project. And it is! But performance spaces are incredibly complex. They welcome large crowds of people in short spaces of time and there’s a ton of engineering, infrastructure, and technology built-in to the building (think about all that technology above and below the stage!) Not to mention the highly technical and specialized backstage support spaces, or the front of house areas where each room finish needs to be both durable and comfortable. Unsurprisingly, because of all those factors, these spaces can also come with a hefty price tag.

Compare the average construction cost of common building types* if you were to build them in Nashville in 2021:

- High school: $230 – $276 per square foot

- Police station: $441 – $530 per square foot

- Five-star hotel: $473 – $662 per square foot

- Mid-rise office building: $484 – $580 per square foot

- Performing arts center: $679 – $848 per square foot

Then, add on the cost of professional fees, permits, FF&E and soft costs, likely inflation over a project schedule spanning several years, and a contingency for potential change orders. All of a sudden, that $50 million budget can get chipped away pretty quickly.

We know our clients want to get the most out of their budget, so our job is to help them understand what is possible. You can build a really great venue with far less than $50 million, and you can build an equally great space with $150 million. The difference is in the details. How many performance spaces are needed? What are their functions and capacities? How much equipment will you need? What level of finish do you want for the rooms? And so, the project planning and design process begins.

If we run the numbers and the budget doesn’t support all the client’s requests, we have to find ways to create efficiencies. Sometimes the solution is to build new venues in phases, allowing work to happen in pre-planned stages while fundraising efforts continue. For existing venues, we can complete renovation work in phases around a performance season, so revenue isn’t lost while the building is closed. Ford Amphitheatre‘s typical performance schedule spans from April-September. So, when their performances ended for the season, our renovation work would begin. Over three winter seasons, we reseated the venue, added a new loading dock as well as audience and performer support spaces, upgraded equipment, and more. Each part of the renovation was pre-planned and run according to a strict schedule, so when the venue was ready to reopen and welcome their audiences back, there was no disruption to the live entertainment experience. Obstacles engender creativity—and this is a good thing!

Other times, the cleanest solution is to create a flexible or multipurpose room to accommodate multiple users in a single space. Knowing who the users are in advance helps us to prioritize the capabilities of the space. With adjustable acoustics, flexible seating and staging, and carefully designed technical systems, a single room can host anything from drama productions to live music, dance, lectures, flat floor events, experimental media, and film screenings. These spaces range in style, purpose, and cost—from the community theatre at Crosstown Concourse to the interdisciplinary learning environment at Duke University’s Rubenstein Arts Center and the multiform performing arts center at Brown University. The demand for these multipurpose innovation centers is growing in school, academy, and university environments, where interdisciplinary education and activities are encouraged, but it’s a trend we’re also seeing in commercial, leisure, and mixed-use developments too. While offering clients an economic and efficient solution of meeting their goals, these highly versatile spaces offer operators the flexibility to further develop their programming as their needs evolve and their organization grows.

Site constraints are also something that can drive the size and shape of a facility. When we were creating a new drama theatre for Northern Stage, we worked within the confines of a prefab Butler Building structural frame. Because the steel structure was unchangeable, our designs involved some creative planning—and multiple iterations of design—to maximize space and optimize circulation, while still providing a dynamic and intimate theatrical environment.

On other projects, like the Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts, the land that the building sits on had been purchased in advance, so the new arts center needed to fit within that pre-determined parcel. An additional complication was the vertical construction limitation—the relatively high water table in Orlando prevented us from building much below ground level and a tall building would push the project over budget, so we had to carefully design the center to fit within both physical limitations.

And, of course, projects involving pre-loved buildings always come with unique site challenges. It’s not always possible to knock down walls or supporting columns because of their structural function. Integrating new materials or technology in historic spaces needs to be done sensitively to retain the interior aesthetic or historic features of the building. And the local community also holds a sentimental attachment to these spaces, so designers need to understand what the community values most about the venue—which often involves surveys and many one-to-one conversations within the community! We’re currently undertaking such an exercise as part of a renovation plan for the City Auditorium in Altus, Oklahoma.

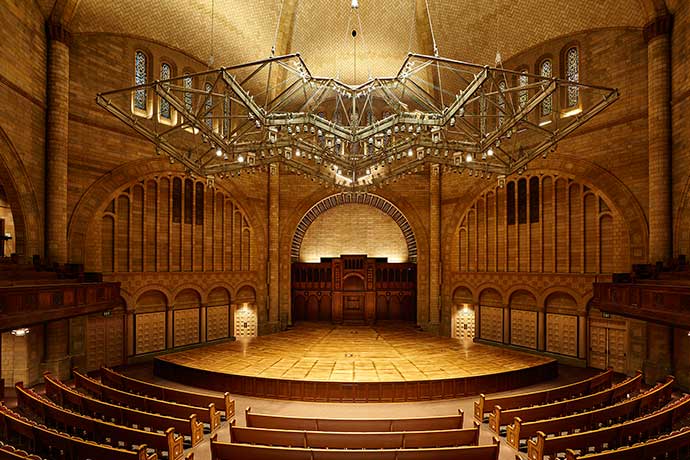

These kinds of projects always give us the opportunity to think outside of the box and do things that wouldn’t typically be considered for new buildings. At Case Western Reserve University, for example, adapting their synagogue to accommodate musical concerts required a sensitive touch. To preserve the historic tiles adorning the room’s domed ceiling, we created an acoustic canopy that hangs from a few strategic places—and we used transparent acoustic reflectors to keep those tiles on display. We also designed flexible staging to reduce the concert platform from 32 feet to only 12 feet when the hall is in use for religious worship. But no matter the building or its story, there’s one thing you can almost always count on when you’re working on these projects—you’ll usually discover unexpected challenges part-way through the project and have to adapt accordingly! And that’s part of the fun!

And, because our goal is to make our world a more welcoming and accessible place, we’re always striving to make our spaces more inclusive for every member of the community. Solutions that don’t think expansively and inclusively, that only consider a portion of the community, are not real solutions. The National Veterans Resource Center at Syracuse University was constructed in accordance with Universal Design practices and includes several features to help users and audiences who live with disabilities to interact with the space and its programs. Those features include bariatric seating, increased row-to-row spacing in the auditorium, and live-captioning displays which help deaf and hard-of-hearing attendees follow presentations more easily. At Alliance Theatre’s Coca-Cola Stage, we designed quiet spaces for people with sensory sensitivities to light, sound, or crowds to watch the action in a comfortable environment. And at the Rochester Institute of Technology, we discovered that no off-the-shelf products exist to allow hearing-impaired actors and stage managers to communicate visually with their colleagues—so we designed a custom system for them!

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to projects, but we enjoy taking a look from every angle to come up with the best solution because it keeps us on our creative toes. We’re always happy to work with clients, no matter what their budget, and we embrace the next unique challenge.

*Construction stats taken from a Cumming Insights construction market analysis in 2021